Reflections on a rapid Mount Everest climbing attempt by IAG guide manager Connor Chilcott

/I woke up to Phura Sherpa handing me a hot towel. It was 2 am. The May air was crisp and cold. The sky was clear and you could make out the silhouettes of the surrounding peaks. I looked up at the Khumbu Icefall to see headlights spanning from top to bottom. I was hoping we were leaving late enough to avoid the twenty-plus person teams heading up that day.

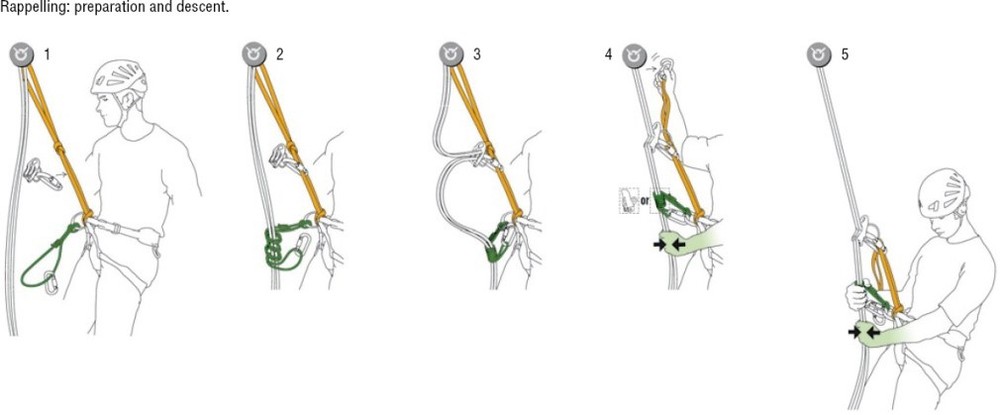

After a short breakfast we headed toward the icefall, passing about 20 people along the way. Things were going well and our team of three.. myself, my guest Joe and our Sherpa, Dorje Sherpa, were feeling great. We rounded a corner and I got a glimpse of the first vertical fixed rope. Ten people were standing in line waiting for their turn to ascend. Progress was slow, the person in the front dropped their mitten. A Sherpa got it for him and proceeded to clip the man's jumar to the rope for him. Then the Sherpa slipped. It was very icy and a precarious place to try and help someone with the most mundane of tasks. But that is the heart of the Sherpa people, they risk their lives to help people achieve their dreams. I then watched in horror as the man ascended the fixed line slower than a competent climber could solo the ice step.

Climbing on loboche east

As I was standing there, I looked around at the place we were all waiting in. There were hanging towers of teetering ice above us at all angles. At any point these towers could collapse, smashing the line of people like ants. Dorje Sherpa appeared to think that standing around there was normal. At that moment I heard a collapse, the beam of my headlamp went from the climber still on the fixed rope to the huge ice blocks coming down the gully just to our left. We had been walking there just 10 minutes before. A team we had passed was in the line of fire, and the ice just kept coming. Dorje closed his eyes and began chanting “om mani padme hum,” a Buddhist mantra. I watched as the ice kept coming and looked at the vertical wall in front of me wondering when the avalanche was going to start flooding over that wall. It never did. The moment the ice stopped, I unclipped from the rope and booked it back down, saying that I was not about to die waiting in line. I ran towards the team that was in the line of fire (they had all been able to move into an ice cave to avoid being killed) and back to base camp under the moonlight. This was just supposed to be a short fun little acclimatization jaunt.

Navigating the Icefall

After summiting Denali last year, I received a call from a long time guest Joe. Joe had always been interested in climbing Mt. Everest but he is a very busy man and for him, time is of the essence. We decided that if we acclimatized at home and exercised using a Hypoxico tent and utilized helicopters for transportation, it would be possible to climb Everest in 3 weeks, house to house. After a ton of training and many uncomfortable nights sleeping at 18,000 feet in our homes, we departed for Nepal. We landed May 3rd and our return flights were set for May 22nd. The next day, we jumped on a helicopter with the hopes of landing in Loboche. Unfortunately the weather forced us down in Namche Bazaar. I was not too bummed as Namche is my favorite village on the EBC trek. That evening my friend Jim and I found some kids who were playing soccer in the mountains. We joined them for a few games and they kicked our butts. This was definitely the highlight of the trip for me.

Plaiyng soccer in Namche Bazaar

The next day we woke up early to catch the first helicopter to Loboche, but upon opening my eyes I felt a nasty chest infection coming on along with chills and body aches. In hindsight, I should have stayed in Namche for a few days but sometimes, especially when I am guiding, I try the mind over matter approach. We flew to Lobuche that day, but the next morning I woke up feeling like death. Considering I was at 16,200 ft, I had to descend and I headed to Dingboche at 14,400. This helped tremendously, and after 3 days of rest I was heading back toward basecamp. My client Joe and our team were already there. On the way back I stopped at Lobuche village for a quick nap, woke up at 1 a.m., and headed toward Loboche high camp. I saw no headlamps, no people just me and the night sky. At daybreak I was sitting eating a snack when a Czech climber was coming up solo. We chatted for a few moments. He was incredibly fit and was acclimating for a first ascent in the range. We climbed together and stood on top of Lobuche East five hours after leaving the tea house that morning. It was a beautiful day and we saw no other people. We ran down the mountain, arriving back at Lobuche village after 6.5 hours on the move. The next day, I headed to Everest base camp.

After the surreal experience of climbing with just one other person I was appalled by the lines of traffic hiking to EBC. The amount of stuff that the porters coming down the trail were carrying was simultaneously amazing and appalling. Some were carrying up to three huge propane tanks. Portering is such a rough job, carrying over a hundred pounds every day. The average wage for a porter is $12-25 USD a day.

Porter on everest

I met with my team after arriving at base camp. Our climbing Sherpa was already up on the mountain heading to the South Col for a second time to deposit oxygen and tents. This was mind blowing to me, as I’ve always carried my own gear on every other mountain I’ve ever climbed. I truly believe if everyone had to carry their own things on Everest, there would be a lot fewer accidents and, yes, significantly fewer summits. Some climbers climb the mountain with a small day pack containing only their oxygen bottle, but to me this means they are not fit or prepared enough to climb the mountain. The climbing Sherpa are the true reason anyone stands on top of Everest.

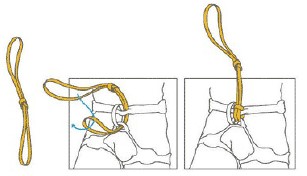

The Sherpa people are an ethnic group that have lived on the borders of Nepal and Tibet for centuries. Growing up at high altitude with walking as their main form of transportation and having to carry all their necessities on foot has made them the strongest group of people I have ever met. I love climbing with the Sherpa, they are so incredibly strong, patient, and happy to be in the mountains. It fills me with sadness that many Sherpa die every year helping climbers and making it possible for people to stand on top of Everest. They do the most dangerous job in the world. The icefall doctors, as they are known, are a team of Sherpa that set ropes and ladders up the icefall. This year the route up the icefall was 9 miles long. Setting ropes and ladders for 9 miles means you are exposed to the most dangerous part of the mountain for much longer than anyone should. After the icefall is fixed the rope fixing team climbs to the summit of the mountain, carrying enough rope to fix the entirety of the route. The rope going from Camp 2 to the summit is the only reason anyone summits Everest. It is also why traffic on the ropes gets so backed up.

Connor ascending fixed lines on everest

Luckily for us the weather was clearing up after an entire season of poor weather. The rope fixing team summited on May 14th and the final day we would be able to summit, with our short time frame, was the morning of the 18th. We headed up and made it to Camp 2 feeling great. No headaches, we were eating well, and we were moving at a good pace. The next day we planned to move directly to the South Col and skip Camp 3. On the way to Camp 3 my guest had an injury resurface. However, we continued on and upon arriving at Camp 3 we looked up to see over 90 people in line heading to the South Col. This was the final nail in the coffin for us. The day before we watched hundreds of people heading to the South Col. We were setting ourselves up for being three of three hundred people attempting the summit. After a long conversation we decided we were not interested in that type of climbing and headed down. This was a bitter moment because I knew how hard our Sherpa team had worked getting the mountain ready for Joe and I. However with Joe’s old injury flaring up and the crowds on the mountain I couldn’t resonate with going up.

The line of climbers leaving camp three on everest

After returning to base camp I then headed to my good friend Ang and Lakpa Sherpas’ home in the village of Pangom. I was immersed in the silence and the tasks of simple everyday life, such as milking the cows and attending their town hall meeting. At their town hall meeting I watched as the 15 villagers paid their taxes. Two hundred rupees per cow, two hundred fifty per horse, baby cows are free (one hundred rupees is one US dollar). Some villagers did not even have two dollars to spare for the taxes so other villagers chipped in, as did I. They may not have money, but there is something to be said about the happiness radiating through this village. It is quiet, beautiful, and they have everything they need. After the last few weeks, I really learned to appreciate this way of life.

by IFMGA guide & IAG guide manager Connor Chilcott

Connor’s climbing achievements are far and wide ranging from Yosemite big wall speed ascents to serious alpine climbing objectives in far flung mountainous regions of the world